So we finished the behavioural economic experiments for the second work package (WP) in my project Patron of the seas and I’m back in Stockholm finishing off paper 1 which is a grounded theory of sukianay (patronage relations in the Philippines) that I put together with research assistants and project participants over the last two years (hectic). But in-field while switching from the first interpretive qualitative WP work package (which was done through various types of interviewing) and going into the data collection and creation of the economic experiments I had some STARK feelings. One week into the experiments I started to reflect big time on the marrying of these two approaches that I am bringing together here. Why am I doing this? Well my friend Simon West has been my interpretive trainer and Therese Lindahl, my other buddy (plus my ex PhD co-supervisor), my trainer in behavioural economics. I basically put this project together as I wanted to work with my friends 🙂 , that’s a major driver for me in research. It just so happens that trying to knit together these two very different epistemological approaches to research also aligns with what the New Normal project is trying to do- which Simon and another great friend Caroline Schill is involved in. Hopefully more to come there- stay tuned.

What have we been up to?

We did interpretive interviews (90 in-depth ordinary language interviews) in 2024 with different types of fisherfolk and fish buyers/traders about their Patronage relationships or patron-client relations (i.e. the socially embedded market relationships that small-scale fisher folk around the world rely on for selling, buying, financing and much more). I took all the data back in 2025 for co-analysis sessions (see Research diary 6). We then used what we learned about what the sukianay means to people in the coastal fisheries of Concepcion, Iloilo to design place-based behavioural economic experiments. We actually set up the interpretive interviews as an entry point into the project and the phenomenon in question- patronage relations in small-scale fisheries. Why? Because the meanings surrounding the patron-client relationship are contested- meaning different things to policy makers, fishers, buyers, managers, NGO’s or academia. An interpretive approach helped us to prioritise the experiences and understandings of the fishers and traders actually operating within sukianay.

What did interpretive research contribute to our economic experiment?

I did economic experiments in 2017 in the same area of the Philippines (with some of the same participants!) so I have the fortunate chance to be able to compare my approaches to the experiment, then vs now. (See An Experimental Approach to Exploring Market Responses in Small-Scale Fishing Communities).

Firstly, I would say the interpretive work was like the wetness of the project (hahah I know sorry I am terrible with metaphors and I don’t want to use AI to get a better one, I just want it to come out natural :P), it provided such depth to design the experiment with or with which to submerge the experiment in. It gave us the best experimental language ever! The words, language, phrasings, social concepts, colloquialisms etc. that we drew from our two year long WP1 made it SO MUCH easier to set up the experiment and specifically the experimental instructions. We struggled with this big time in 2017, to find the right words in which to introduce the decision space which we create for fisherfolk to make those experimental choices in the most real way possible. This time round I found myself even correcting the words of the research assistants who weren’t involved in WP1 but who were working with the experiment. Although they were students of fishery science and from Iloilo they did not have the specific language of the Concepcion fisherfolk. This made me reflect a lot as a foreigner/westerner/outsider/”kana” coming into someone else’s system (yet agaainnnnn- but where is “my system”??) that yes I’m aware of who I am but this approach to research allowed me a window into the fisherfolks’ culture that you don’t get from more positivist social science. A science which goes in with surveys and close ended questions about specific topics (which is needed in certain situations!). But of course I had the absolute luxury to be able to just go in and ask big open ended questions thanks to my Swedish funding!

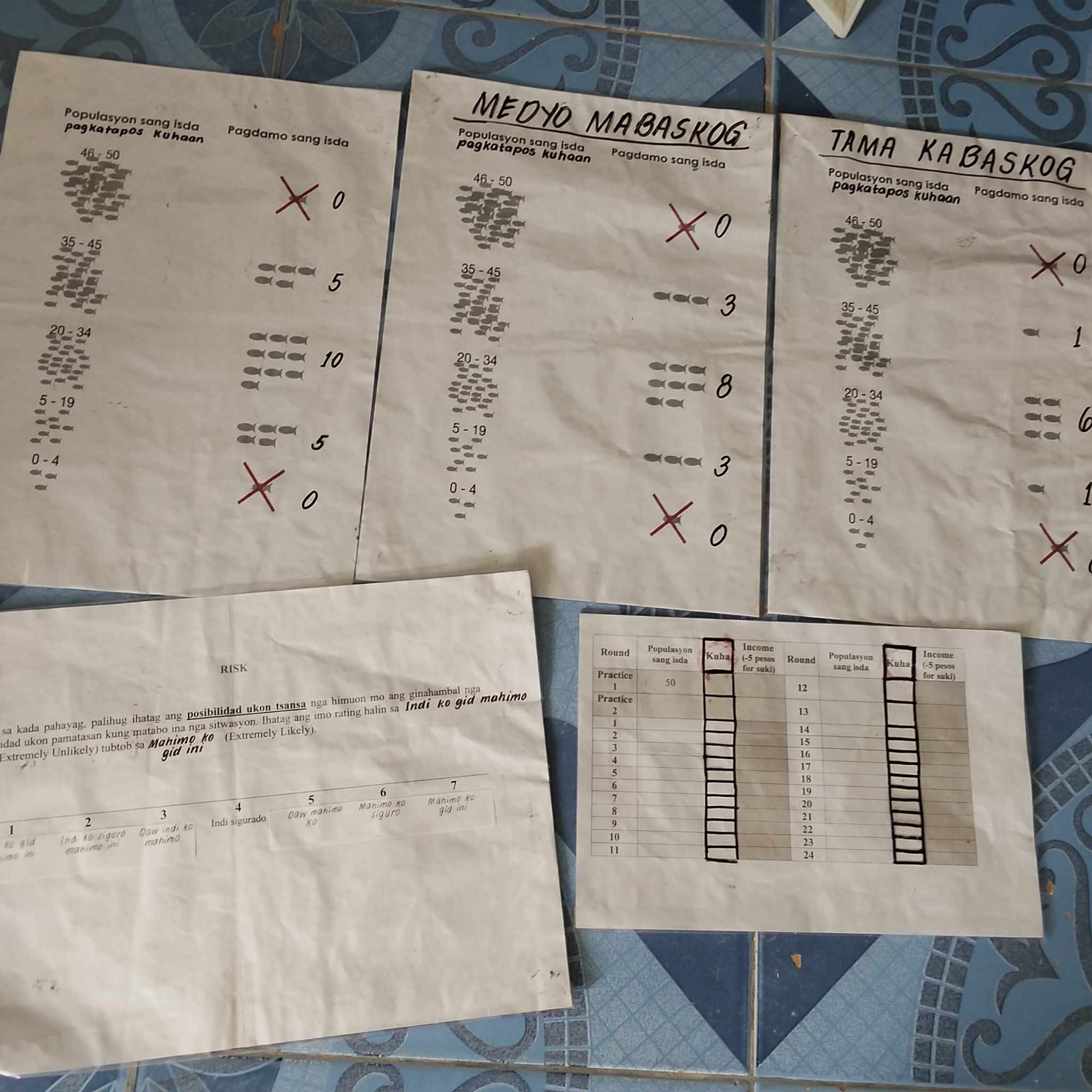

Anyway that was a sideline! BECAUSE for the 2017 experiments I hadn’t spent the time looking through the lens of language, ordinary language, nor had my collaborators or assistants, so we spent a long long time creating all our materials. Going into the design phase of these 2025 experiments, I was at a micro-level of analysis, thinking through what words had what connotations and pulling out key socio-cultural concepts such as “huya” (shame, shyness, embarrassment) or “salig” (trust). So it was much lighter work creating the experimental set-up and the post-experiment survey. I knew what thoughts would arise if I phrased a certain question in a certain way with a certain concept, so then I could really get to the “meat” of a specific area I wanted to know about .e.g willingness to leave a suki. The experimental context was so much more relevant/meaningful and weighted for participants to play the “hampang” game (as we called it so they wouldn’t think they were going into a lab). I literally took the same words that fishers used in WP1 to make the experiment with, not words from people who do not live there. I was able to, as I said to Simon, “ground the shit out of the experiment”, compared to before. I think this really assisted fishers to able to make their decisions in a less hypothetical way. We were able to embed the experimental in a world that made sense to them and with their language. People walked us through environmental/anthropogenic changes and what that meant for them and their patronage relations in WP1 and then the experiment was designed to understand fishing decisions under change- framed within the sukianay.

Sitting down with the results of the exit survey or post-experiment survey is 1000 times less frustrating now as I can understand more the “behind the scenes” of the words they use- which you could never do with this type of survey data alone. I am much more confident in the meanings derived from the survey now. Although one would always collect complementary data for an experiment, both qual and quan, this type of interpretive data is different and its hard to explain, its got a depth to it that I never had in any qualitative work I did before. It kind of digs into or is able to explain social action and behaviour much much more. Like running surveys after experiments is necessary to collect the social or whatever explanatory variables you need but they can be dry if you are not sure how the social/cultural concepts that people might drop into their responses have an effect on what they do. For example if they mention “utang nga kabalaslan” in a survey context (debt of gratitude or debt on the inside) you only can assume then how it might work in their fishery and market relations (if you haven’t specifically asked what it means in an interpretive setting), but thanks to WP1 we have a huge amount of data that theorizes how kabalaslan works and what it actually does- from the horses mouths so to speak 😛 Yes you can assume how it works based on previous experience in the field, through gleaning its understanding, but its not the same thing as sitting down and asking- can you explain what that is, can you define that for us, can you give an example of how that works/plays out for you in your experience? My research assistants were desperate to explain these types of cultural concepts to me- but are they fishers or traders in a sukianay?

The tiredness was so real during the experiments, a different tiredness from interpretive work. In WP1 we just rocked up with pen, paper and a recorder (and my kids a lot of the time) and just hung out with people and chatted. Although this did of course drain me emotionally because in each interview I kind of gave a piece of myself up, so after 3 in a day I was done for. The focus for that hour of interview, the creation of that discursive connection, the concentration, the thought process behind each prompt or question…. I was drained. But for the experiments we had to prepare A LOT and the physical plus mental toll it took on me and the team was obvious. Experiments are very physical, and often the research assistants I work with would be more city gals who don’t do the physical 😛 (which is interesting in itself, those that are associated with the University or who have studied there are of a certain class in which exercise or doing more physical things is not a particular tradition- yet)

“….like we have to go back and forth, and it gets really tiring, sometimes, most of the time, some people [participants] pity us, and people actually pity us. People actually the participants actually pity us when they see us coming back and forth and it’s kind of far, yeah…” (Research assistant, debrief interview)

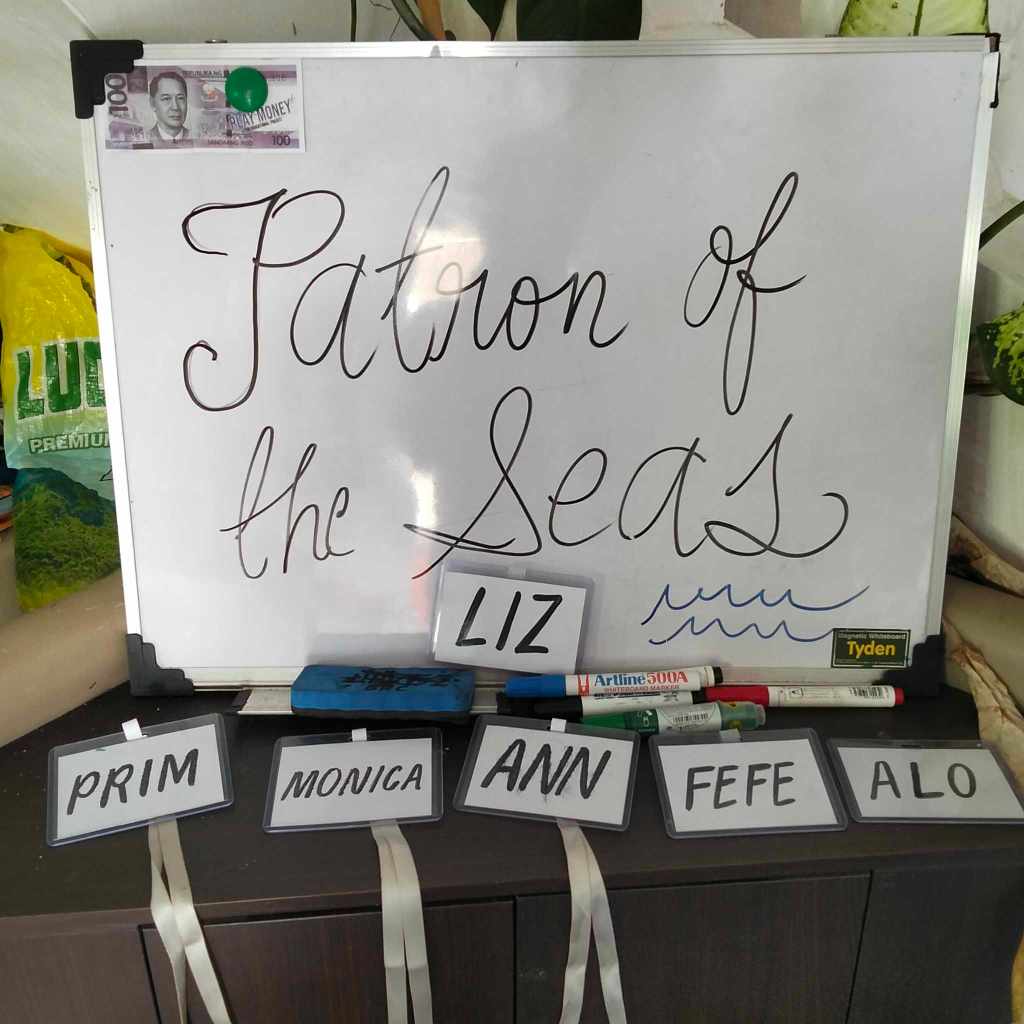

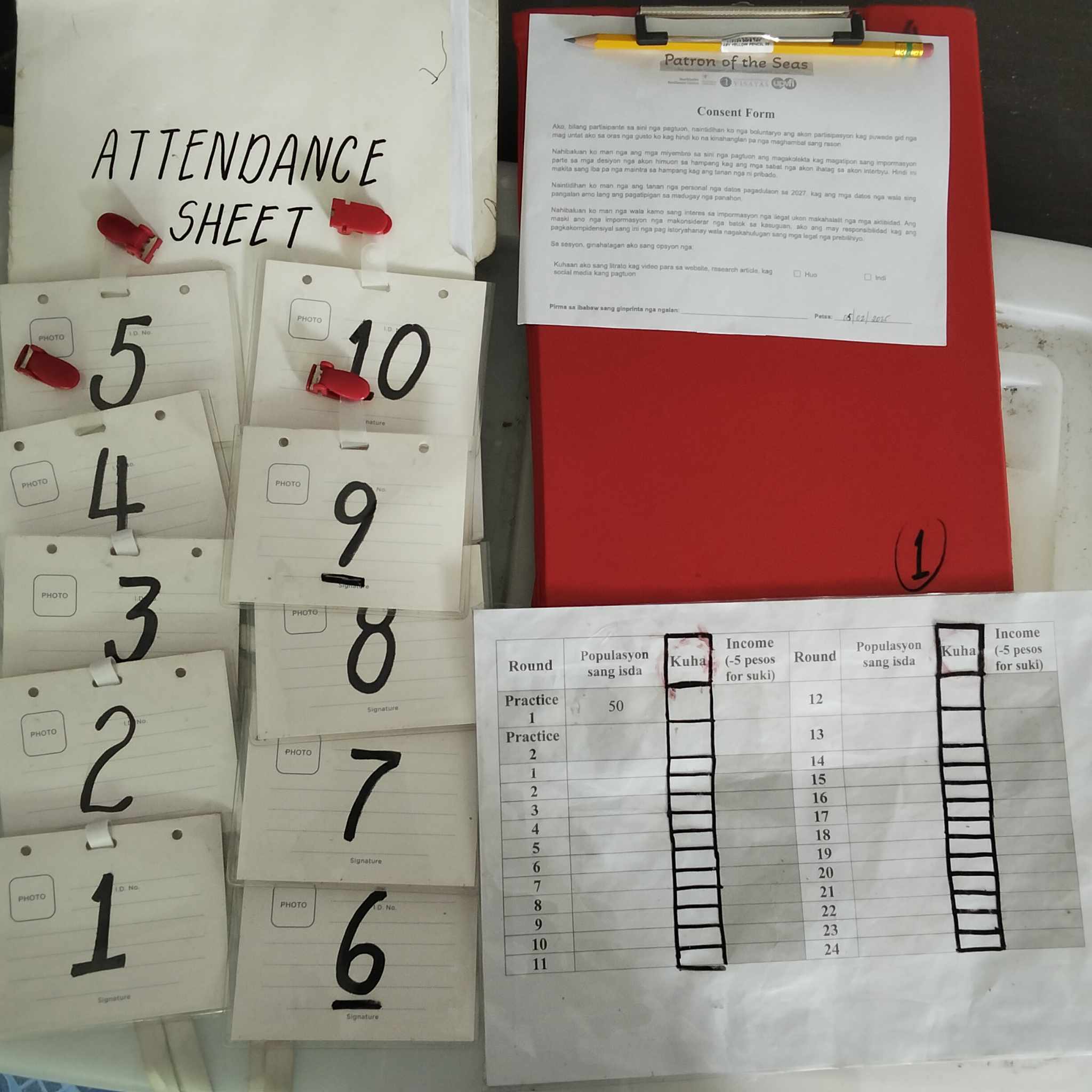

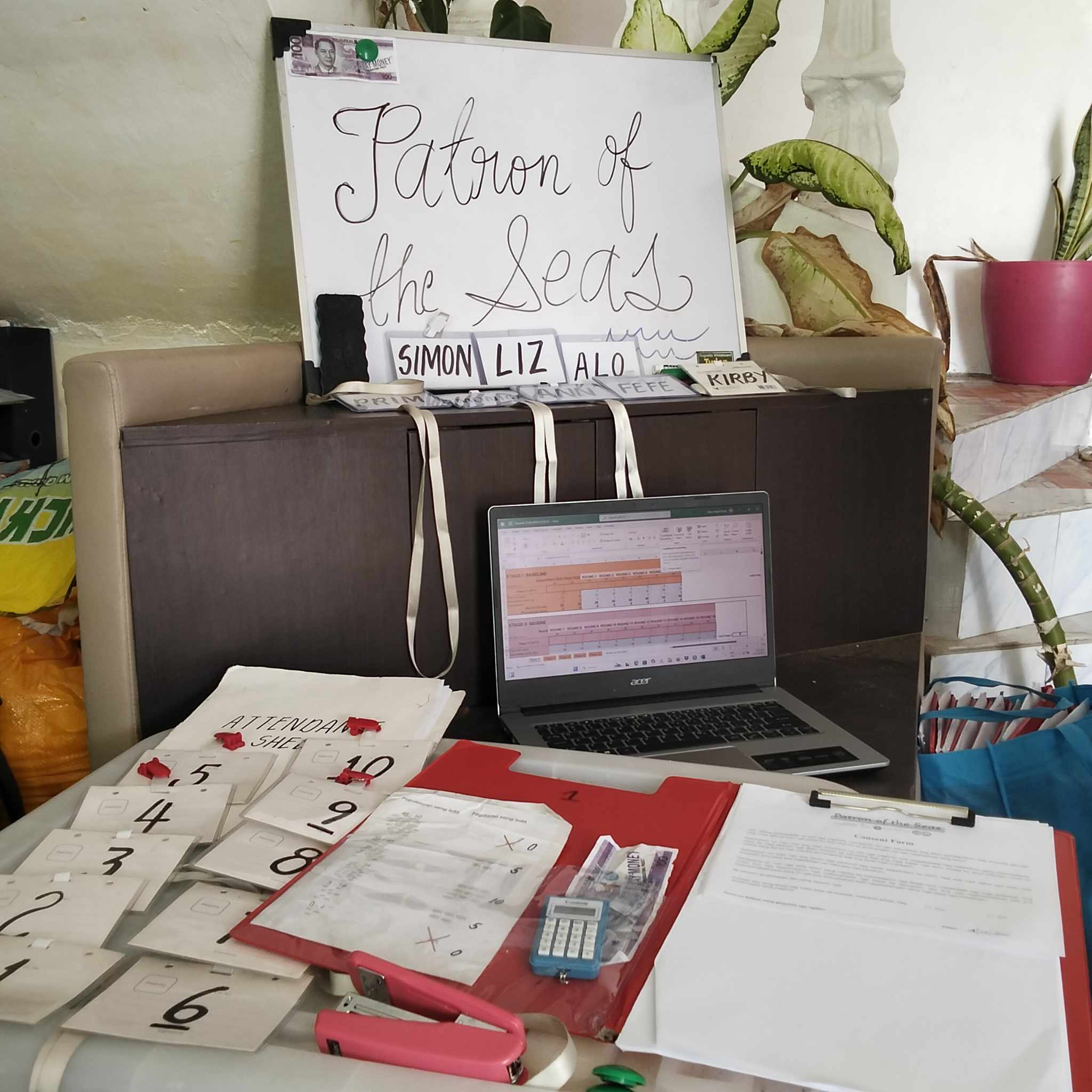

We didn’t use money for the experimental pay-off we used groceries, so we had to stock, organize and take with us a little store for people to get their products everyday. Each night we were up late weighing rice, packing grocery bags, correcting experimental instructions and preparing the equipment for the next day- the whiteboards, the paper, the pens, the clipboards, the number badges, the snacks and water for participants, the coffee, the coffee mugs, the hot water thermos, the surveys, the decision cards, our own bags, our lunch, toilet paper, voice recorder, batteries, risk cards and the list goes on.

As the leader of the experiments I had to make sure everything was standardised across all 25 sessions (10 people per session, sometimes more), from the words and body movement of the facilitator to the emotions on the faces of the people calculating the income of fishers per round of the game (which included me) to the steps of the experiment. I basically had to turn into a big BEATCH! Sorry to say. It was such a different relational experience than the interpretive interview work. I had to tell the field team what to do the whole time, to ensure data quality, but because of this constant overseeing I wasn’t able to connect with them on a deeper level, I felt like we weren’t coming together to make the data, but it was more of a pyramid. With me barking annoying orders from the top! But you have to be annoying otherwise whats the point to get shit quality data?! But it was not fun for anyone, especially me, as this is really not my personality, I don’t like bossing people around. It brought out such a different side to me than the lovely chill interview and co-analysis sessions we had with participants during WP1. When interviewing with interpretive ethic then you really need to have a good and deeper relationship with the research assistant, because they help you create the space, the conversation and ultimately pull out the meanings that people give to things/concepts/relationships/experiences (and nice vibes)! Of course the research assistants helped me to make the experimental data too but it wasn’t in a co-produced type of way, the emergence of data wasn’t so dependent (or even at all) on my personal relationship with them. It made me think- am I more suited to a certain type or way of doing research? Does one fill my soul more than others?

As well as not being able to connect with the research assistants (because of time, logistics and the amounting of bossing I had to do) I had to remain separate from the research participants. We created lab-in-the-field or framed field experiments so elements of the sessions had to be controlled in this real world setting and repeatable. Therefore I couldn’t go and start talking away to all the participants and creating different conditions/influences across sessions. I had to remain in the background doing all the calculations on a laptop, which made me feel like such a white colonialist. To sit there at a distance to everyone and have “control” over their decision cards, to be associated with the fishing incomes and money, even it was part of the game, was a bit gross and colonial for me. It was not comfortable. The nature of the experiments too is quite extractive, it takes ages, the session was 3 hours in total which is A LOT to ask from people. Like it all felt very yucky. In the interpretive interviews they could be doing other tasks or be in their houses. So you can’t do this type of experimental method just anywhere, you have to be much more selective and sensitive as to where or who you do it with (also as there are “benefits” involved which is typically money) e.g. the history of research there, their ability to say no. I did get around the disconnect with participants by starting up mini-interviews before the participants jumped into the post-experiment surveys, after a few sessions we started doing these short interviews which focused on people explaining their decision-making in the game. So I was able to have a bit of craic at least! It also was more enjoyable for the research assistants to have this open space to chat to participants and continue this through the survey, see what Prima said in the quote below;

“So I just feel fulfilled because with just knowing their stories, sir, like for example, for one participant that I interviewed, she was a solo parent, and she had like 11 children, and she….and most of them have already graduated college, and she managed to do that just by herself. I was so happy for her…One participant, said that he wanted a sustainable fisheries so he doesn’t really think of the income. He just wants to have enough income just to get by. Yeah, and I don’t know, like, it just touched my heart. Many touching stories, sir, when this comes out through the surveys at the end, surveys, get to know them better.“

We also did a de-brief interview with the research team- which included Tito Alo (our host and guide anytime me and my family are in Iloilo) to get some insight into the team’s experiences and the “chismis” gossip going on behind the scenes with participants e.g. what did they think of us, how did they get recruited. Being able to have the complementary experimental methods and apply the interpretive ethic or attitude I had learned from WP1 (which is something I will carry from now on) was something that made me open to the “behind the scenes” of the experiment, and the importance of capturing the how of experimental data creation- so I could ultimately better understand what it all means. After WP1 and my first encounter of interpretivism I am MUCH more sensitive to what I am doing, how I am doing it, how people will interpret what I do, how I will interpret them, how will we interpret the results and so on. I nearly had an allergic reaction when the field team first started off their interviews after the experiments as I could see they just weren’t leaving the space for participants, to think and respond, they weren’t reading the body language and they just kept interrupting people and finishing their sentences. I kept repeating myself till I was blue about how we need to be ok to wait in silence, to just stay quiet but it was very very hard for the field team. And this has been the same case for the many research assistants I have worked with in the marine social science/fisheries space across the world. I gave the field team a tip which worked in the end- if I just hear your voices in the recordings then we are not getting any data in fact we are losing data, what the participants say and how they say it is like little gems being dropped all over the transcripts, if I open a file and its just your voices interrupting and finishing their sentences then I literally don’t get any data. Mean amn’t!? Sorryyyyyyyyy

Even though the methods used by each approach (behavioural economics and more classic interpretivism) seem worlds apart the “essence” of their aim was the same in this particular project. The interpretive work provided the in-depth grounded understanding of an economic relationship much beyond sales transactions, prices and products while the behavioural economic approach also aimed to move beyond this idea of homo economicus to test how the same participants (plus more) made decisions in response to resource changes.

An interesting question to dwell on though is what if we did the experiments first and then interpretive research?

See some pics below 🙂

Leave a comment