Middlemen* as critical social-ecological linkages in small-scale fisheries

*not always men and often referred to as intermediaries, traders or patrons among others

IN A NUTSHELL

Efforts to curb unsustainable exploitation of marine resources often focus on restricting fishers’ effort. But increasingly global demand can create exogenous pressure that is hard for operators in local systems to withstand. Hence, management must extend up the commodity chain. Here we focus on one critical link in this chain, the middleman-fisher bond, which can aid in channelling sustainable practices but can also lock systems in unsustainable trajectories.

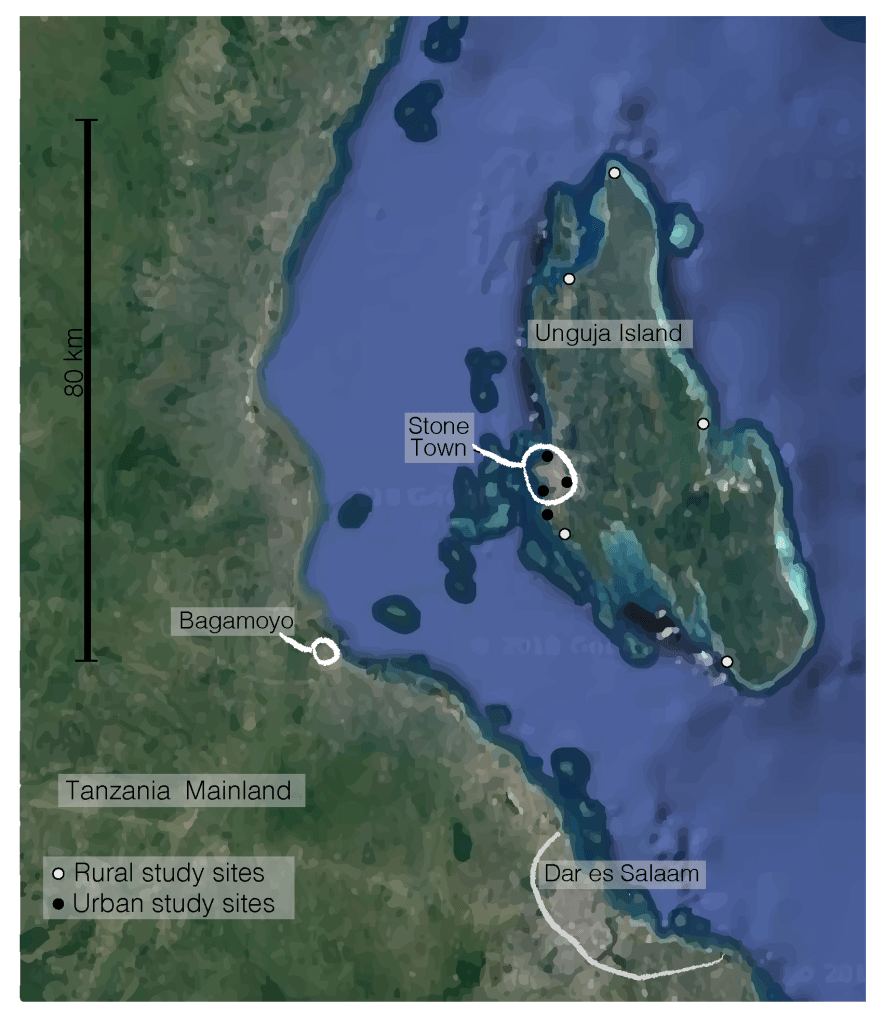

Sites

Phillipines & Zanzibar

Back ground & theory

Globally, fisheries are believed to face a potential crisis (1) while simultaneously the trade with marine fish is increasing and growing amounts are exported to Northern countries from tropical marine ecosystems (2). The industrial fishery and its environmental effects (e.g. 3) has been the target of much research but to date the link between global trade and small-scale fisheries (from hereon SSF) has remained relatively unexplored. Despite this, we see increasing export of fish, potentially accelerating unsustainable fishing practices locally, and also increasing trade in species which are directly linked to key ecological functions on coral reefs and related ecosystems, fished by small-scale fishers (4). Efforts to curb unsustainable exploitation in SSF commonly focus on restricting fishers’ effort through various means, such as MPAs, catch quotas, etc (5). However, fishers are often constrained in their ability to change behavior due to international market structures, weak bargaining power, etc. Also, increasing global trade can create additional exogenous pressure through economic incentives which are hard for operators in local systems to withstand (6). Hence, management must extend up the commodity chain (7). An important link in this chain is represented by traders, so called middlemen1. These agents form the most direct link between small-scale fishers and global markets and through social norms and credit arrangements they commonly develop institutions which strongly influence resource exploitation with effects on local ecosystems (4,8). Middlemen provide small-scale fishers with incentives and access to markets, as well as social insurance mechanisms through credit arrangements (8). Such close relations between fishers and middlemen are well described for SSF (9). However, focus has been almost exclusively on the social and economic implications of such arrangements (e.g. market effects, access and prices). Little attention has been paid to the effects of these relations on ecosystem dynamics and their capacity to generate services for human wellbeing; that is, linking economic and social relations between fishers and middlemen to ecological outcomes (8). Our previous work on fisher-middlemen relations has shown that credit arrangements are common and that fishers are often bound by reciprocal agreements during periods of lower catches, providing short-term stabilizing social effects. These arrangements create incentives that disconnect resource extraction from ecosystem dynamics and impede development of sustainable use practices (8). Such complex interplay between social and ecological components in a system has been termed “social-ecological traps” (10). The concept illustrates the fact that a fisheries system can become locked in a situation where social and economic relations prevent a shift to more sustainable practices, thus perpetuating a state which risks further undermining both resource base and the social situation of those depending on it. The mechanisms behind this are closely linked to the idea of poverty traps; situations where low income among fishers creates economic dependence that influences decisions about production, marketing and extraction practices. This can lead to situations where fishers are unable to mobilize necessary resources to overcome shocks or chronic low-income situations, consequently remaining in poverty traps (11), leading to continued extraction pressure and potentially deleterious effects on ecosystems. Breaking such traps, or lock-ins, can be critical to transforming towards more sustainable futures but requires a better understanding of both the social and ecological feedbacks that govern local systems, as well as how these interact with external pressures, such as global trade. Middlemen may play an important role in directing such feedbacks, mainly because of their structurally important position as mediators between markets and producers, as well as the nature of their bond with fishers.

This project ended in 2018 with my PhD thesis: ” Catching values of small-scale fisheries A look at markets, trade relations and fisher behaviour”. Click the title to download the PDF of my thesis or read and watch some of the main highlights here.

References

1. Garcia, S. and De Leiva Moreno I. The state of the world fisheries and aquaculture. Rome, FAO. 2000

2. Delgado, C. et al. Fish to 2020, Supply and Demand in Changing Global Markets International. Food Pol Res Inst and WorldFish, Washington, USA. 2003

3. Frank, K. et al. Science 308, 1621-1623. 2005

4. Thyresson, M. et al. Coastal management. In press

5. Berkes, F. et al. Managing Small-Scale Fisheries: Alternative Directions and Methods. Intern Dev Res Center, Ottawa, Canada. 2001

6. Lambin, E. and Meyfroidt P. Land Use Policy 27, 108–118. 2010

7. Hughes, T. et al. TREE 25, 11, 633-642. 2010

8. Crona, B. et al. Marine Policy 34, 761-771. 2010

9. Platteau, J.-P. Abraham, A. Journal of Development Studies 23, 461.1987

10. Steneck, R. Current Biology 19, 3, 117-119. 2008

11. Carter, M. and Barrett C. Journal of Development Studies 42, 2, 178-199. 2006

This work was made possible through the generous contribution of SIDA (The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency) through Grant number 1425704, by MISTRA funding to the Stockholm Resilience Center Grant No. 1953001 and funding to the Global Economic Dynamics and the Biosphere program by the Erling-Persson Foundation