A look at markets, trade relations & fisher behaviour

My PhD thesis in Sustainability Science from the Stockholm Resilience Centre was defended in November 2018. In the video below you can listen to some of my main findings, with some very bad filming from my field sites in the Philippines and Zanzibar 😛 Or you can download the thesis here. This PhD was part of the STEP project run by my main supervisor Beatrice Crona. My other two supervisors were Tim Daw and Therese Lindahl– the best supervisory team ever! This informal video is a short summary of my PhD thesis, put together for friends and family for communicating some of my main findings (with very dodgy footage from my phone :P). Thanks to Sturle at Stockholm Resilience Centre for helping me put it together

Summary

This thesis explores small-scale fisheries trade, markets and the accompanying relationships. It does so to understand how they contribute to human wellbeing and ecosystem health through fisher’s behaviour in the marine environment. The capacity of small-scale fisheries to provide for fisherfolk and wider society is currently challenged by human induced ecological threats such as overexploitation and climate change. Small-scale fisheries are increasingly incorporated into the global trading system, which in part drive these ecological changes. At the same time these fisheries are important providers of food and livelihood security for millions of people worldwide. How to realise better fishery governance approaches and enactment is therefore paramount. This thesis attempts to address knowledge gaps in governance and research that centre around the market and actors within it- an area little included in governing fisheries. I draw on the value chain concept and use a mixed methods approach to address three gaps. First, the structure and functioning of small-scale fishery markets and relations. Second, how benefits are distributed in the market and affected by trade relations. Third, I examine how relations and benefit distributions influence fishing behaviour. Case studies are used throughout this thesis drawing on empirical work done in Zanzibar, Tanzania and Iloilo, Philippines. The role of global seafood markets is additionally recognised as a driver of change in all four papers of the thesis. Paper I shows that extending the value chain to combine economic and informal exchanges identifies a wider range of fishery-related sources for human wellbeing within seafood trade. It also highlights more marginal players. Paper II demonstrates how actor’s abilities to access economic benefits are impacted by local gender roles and social relations. But these intersect with their value chain position and end-markets. In Paper III local norms appear to play a role in fishing behaviour, more so than market incentives. These dynamics are explored through behavioural economic experiments. Finally Paper IV examines how patronage can have contradictory influences for fisherfolk vulnerability and adaptability. It can also create tensions for overall system resilience when considered at different scales. Overall the thesis contributes to a better understanding of the local to global drivers and interactions in small-scale fisheries trade. The thesis also provides insights into some of the factors influencing the distribution of fishery related benefits. These aspects have all been cited as vital for designing strategies for improving the wellbeing of people reliant on fisheries.

Keywords: small-scale fisheries, value chains, gender, seafood trade, global markets, patron-client, human wellbeing, benefits, markets, local social dynamics.

Scope of thesis

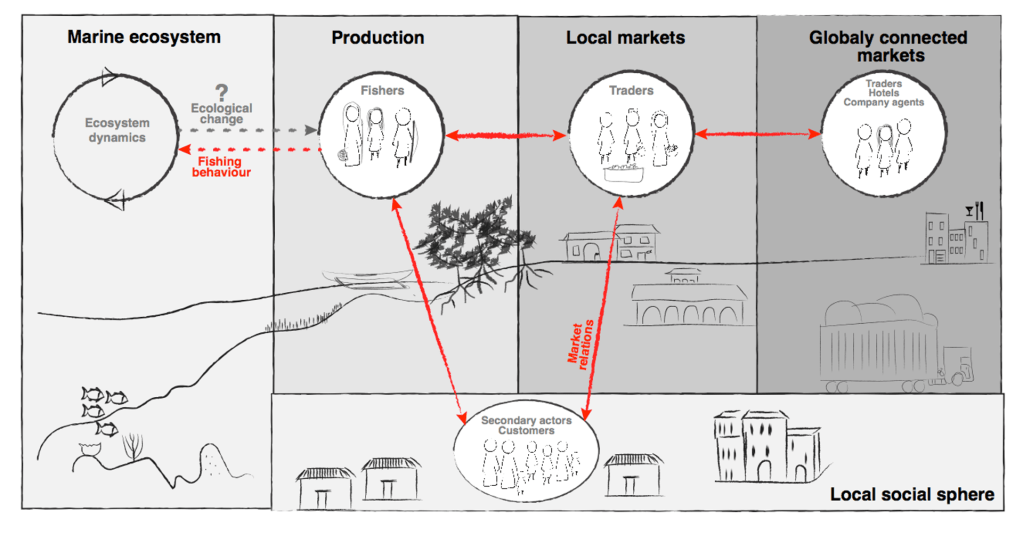

This is how I saw my system and basically how I conceptualized the people and interactions I was studying So, moving left to right, I have the marine ecosystem, production, local markets- like those within the locality or province or country, and then I have globally connected markets which include tourism and export. The local social sphere at the bottom represents me trying to embed my fishery in the broader society. The people I study are drawn in the little white circles. So from left to the right, I study the fishers, the traders which include buyers, processors, dryers, hotel traders, company agents and then the secondary actors, at the bottom of the figure, like auctioneers, helpers around the markets and customers The interactions I study are IN RED. They include the relationships between all the people I just mentioned but also between the fishers and the environment through their behaviour, driven in part by the market and relationships.

6 Key Findings

- Incorporating non-sales transactions into the VC (value chain) provides a better description of the market’s safety net functions, especially for more marginal or peripheral actors.

My work in Zanzibar highlights a layer of market relations in the SSF VCs that are not generally captured by traditional VC or economic analysis (Fabinyi et al. 2018). These relations centre on assistance and reciprocity and include exchange or provision of cash-gifts, food, seafood products, services and loans within VC nodes, between them and beyond the VC. Tracing these interactions showed a wider influence of the Zanzibar VC, highlighting its horizontal elements – local social relations. It also brought to light previously unidentified actors, beyond fishers and trading-agents, that play a role in the market place. These actors, referred to in Paper I as auxiliary actors, are important to capture. A poor understanding of their influence on and from marine resource related benefits, risks undervaluing the contribution and importance of the environment to local livelihoods (Fröcklin 2014). This can skew efforts for conservation and poverty alleviation with negative effects for overlooked groups in society (Daw et al. 2016). Certain actor types (e.g. rural actors, especially fishermen using larger vessels) were more engrained in the Zanzibari informal assistance network. While others, like female urban traders, remain on the margins of these exchanges, leaving them potentially more vulnerable to short-term fluctuations in the fisheries and markets. Paper II shows that the safety-net function of assistance networks operated differently across cases. For example, exchanges between fishers and traders in Concepcion were limited to economic transactions and asymmetrical financial support from traders to fishers. In Zanzibar, fisher-trader relations were often reciprocal and spanned a wider array of exchanges, such as food and favours. Concepcion also differed from Zanzibar in that repayment of loans or other types of assistance (Concepcion fishers also exchange non-financial help) is typically required both within and between nodes. In contrast, gift-giving exchanges tended to more often mark trade interactions among Zanzibari actors. This gifting seems to reinforce social standing within the market environment. Such findings have commonalities with work by economic anthropologists and sociologists where actors in an economic environment are not only concerned with maximizing their production and income but also social standing, reputation, norms and rules of the context (Granovetter 1985, Ortiz 2005, Smelser and Swedberg 2005). Market related gift giving plays an important role across Tanzania’s agricultural markets (Eaton et al. 2007), and in the broader Swahili society (YahyaOthman 2009). Most societies at the local scale have evolved social processes, including customs and reciprocities, that are interlinked with economic exchanges (Smelser and Swedberg 2005). Such processes can promote human wellbeing in addition to ecosystem services (Butler & Oluoch-Kosura 2006), and thus are important to present in VC contexts. These results highlight the horizontal dimensions and safety-net functions of the VC, and how they are not easily separated from financial transactions or local social norms (Fabinyi 2013, Fabinyi et al. 2018). These are generally not analysed in relation to VC positions.

Paper I and II therefore contribute to a more realistic conceptualization of SSF markets. They present the importance of non-financial value creation in the VC for a better understanding of benefit flows in this context. I contribute to more recent work in commodity-chains and SSF that incorporate the importance of these social relations in market organization and operation (Fabinyi 2013). Specifically, I take a next step by mapping these relation-types as assistance and reciprocity in combination with the VC. These types of nuances are important as governance interventions with a poor understanding of the informal less visible market interactions risk undermining vulnerable actors’ options for short-term livelihood security.

- The nature of patronage differs across cases but in both places social norms create inflexibility that extends through the value chain.

Like previous work Paper I and II show the mutually beneficial nature of patronage for fishers and traders, in my case characterized by the distinct Swahili and Ilongo settings [c.f. (Stirrat 1974, Lawson 1977, Platteau and Abraham 1987, Platteau 1989, Pelras 2000, Máñez and Ferse 2010, Ruddle 2011, Ferrol-Schulte et al. 2014, Nurdin and Grydehøj 2014, Wamukota 2015, Miñarro et al. 2016, Bailey et al. 2016)]. Patronage in Zanzibar appears to be of a more symbiotic nature than in Concepcion. Zanzibari patronage is marked much more by reciprocity, which patrons (nearly all male) and fishermen use for maintaining food and livelihood security. Traders often receive loans and fish from fishers [c.f. Keat 1976 in (Lawson 1977)]. The majority of these traders, whom, relative to Concepcion, are small-scale, capital-poor and lack infrastructure (e.g. ice, storage, transport, etc.), use such relations for providing the economic margins on which they can operate. The contractual arrangements and PC in both cases are marked by influence from the wider community environment through social standing, expressed as the unwillingness to ‘lose face’ by ending an arrangement [c.f. (Platteau and Abraham 1987, Johnson 2010)]. In Zanzibar, traders must fulfil contracts with consumers outside of trade, thus extending the influence of local norms like sales arrangements downstream beyond the fisher-trader link. In both countries actors (both fishers and traders) felt they could not end their downstream arrangements. Ultimately these results highlight that prearranged transactions can create inflexible structures when coupled with the broader social processes and can extend through the VC. This is interesting because it emphasizes patronage as a feature of the entire (local) trade network – not just of a single VC link. Social and business pressures, as well as debt relations, are intertwined throughout the trading networks, possibly affecting the ability for the entire SSF to change and adapt.

- Chain structures and levels of contractualization within the two cases differ vastly, giving rise to distinct income inequalities and distributions. Yet fishers capture a similarly low proportion of local wealth regardless.

In the Philippine system, where Concepcion is representative of other Visayan seaports, contractual arrangements dominate nearly all market interactions. Trading agents – brokers and buyers – are relatively few in number. This arrangement exhibits the highest inequality at the country level (according to the Gini coefficients and Lorenz curves), also amongst trading actors, signalling the capture of wealth by a few.

The market in Zanzibar is structured quite differently. Like other East African agricultural markets they are characterized by smaller product quantities, larger numbers of buyers or traders, frequent spot-market exchanges (auctions or random sales) and limited coordination (Eaton et al. 2007). Zanzibar traders with contractual arrangements, whom are primarily men, reap higher daily incomes than their freelancing peers who sell ad-hoc. It could be that their prearranged customers (hotels and local consumers) demand much higher volumes than ad-hoc sales, which requires a higher level of coordination and performance. The pattern differs among fishers where there is little difference in incomes between those with and without patrons. Fishers in both cases show similar within group inequality, regardless of different markets or transaction types. These types of results are expected as they show producers, regardless of connections to international export or better market infrastructure, capture a similarly small proportion of wealth from their system. Though not strongly connected to international export, Zanzibar is linked to global trade dynamics through international tourism. Traders that have managed to tap into this market, earn more than their peers or fishers, who have not. Thus, a certain few traders can capture wealth with high value market opportunities, but the majority of VC groups are excluded as a result of high barriers to entry, both economic, such as financial capital, and cultural, such as gender roles.

- Gender impacts daily income and participation in both places

according to VC position.

One cultural-related barrier to market participation and/or benefit acquisition in both sites is gender. The roles of men and women in the market are deeply entrenched in local gender identities linked to the broader socio-cultural context (FAO 2017). In SSF-related studies in general, women are often presented as secondary, marginal, and more vulnerable players (Tindall and Holvoet 2008, Westerman and Benbow 2013, Brugere and Bodil 2014, Fröcklin 2014). Results show that in both cases, being a woman impacts benefit capture depending on VC position and activity. For example, I found that women participate in all nodes in Concepcion, though as fishers they earn less than men. In Zanzibar, women operate separately to men in distinctly female nodes, but this does not statistically impact income as there are many male traders who also deal in low-value fish trade as they do. Zanzibari female traders in general rarely either connect to the higher value tourist industry for cultural (Demovic 2016) and capital reasons, nor have patrons. However, both are mechanisms for better income according to my results. When they operate in a similar fashion to larger male traders (transporting, icing, etc.) they capture higher daily net incomes than many traders in the sample. Formal governance in Zanzibar and the Philippines, like SSF related research in the past, view women as minor participants in SSF VCs (Siason 2000, Fröcklin 2014, Kleiber 2014, Williams 2016, Pastor 2016, Pavo 2016) yet women do not necessarily conform to the stereotypical notions that external actors, such as officials or researchers, often impose on them. For example, Concepcion women fish on commercial vessels and run large broker businesses. Zanzibari women can earn higher incomes than many men when dealing with transport options and trade-facilities. Although gender is a strong organizational category in many low income agricultural VCs (Bolwig et al. 2010, Riisgaard et al. 2010, FAO 2017b), deviations exist from the dominant narrative. Evidence for this occurs across west African SSF, for example see Browne (2002) or Udonga et al. (2010).There is evidence in both Zanzibar and the Philippines that women are gaining ground, e.g., in positions and numbers, in the SSF market environment. However, the question remains if these examples are simply cracks in the dominant narrative or future trends in VC participation for women. Gender alone does not drive differential benefit capture. Instead it intersects with different VC dynamics as well as other social factors and need not be singled out if researchers are to better understand actor’s long-term VC positions (Wosu 2017).

In summary, these findings contribute to the fisheries-trade-poverty debate in highlighting how characteristics of different actor groups in the VC impacts their potential to earn income and connect to higher value global trade options (Wamukota 2015).

- Short-term fishing-related decisions are likely shaped by gender roles but not necessarily strongly influenced by economic incentives such as price.

Paper I and II shed light on how individual characteristics drive benefit capture, which in turn may motivate or influence decision making in the market. Paper III takes a step further towards understanding such resource-use decisions, by using PC (patron-client relations) and export markets as two structural features to test market decision-making with an experimental approach. A price rise, used as a proxy for a global market connection, did not predict fishers’ operational loan taking and consequent fishing effort in the experiment. This rhymes with other studies demonstrating a limited response of fishers’ to market incentives (Béné and Tewfik 2001, Salas et al. 2004, Abernethy et al. 2007). In my case gender appeared as the only predictive variable of fishers’ experimental behaviour- which did not relate to gendered risk preferences. Men went bigger than women throughout the experiment regardless of economic or market incentives- both in their interpretations of catch rates as well as their loan choices. Such results reflect the fact that fisher’s market responses often appear to be complicated by individual and collective constraints like masculinity roles, peer pressure, fishing skills, and by the general socio-cultural context of the fishery (Dumont 1992, Russell 1997, Béné and Tewfik 2001, Fabinyi 2007). Paper III adds to this body of work.

While patrons have been cited as influencing increases in SSF production in the literature (e.g. Máñez and Ferse 2010, Crona et al. 2010, Johnson 2010, Ferse et al. 2014) I did not uncover significant empirical evidence for it in an experimental field setting, using price as a mechanism. However complimentary data collection highlights two influences of patronage through financing. Firstly, over half the fishers sampled would change their spatial fishing effort if offered a bigger loan from their patrons by traveling further. Secondly, debt is closely coupled to fishing activities as fishers cannot follow better market prices or conditions without paying off their loans. Thus patronage drives exploitation in this way. This type of theoretical and empirical knowledge on the connections between seafood trade and SSF dynamics can promote an understanding of how insatiable global seafood markets may push SSF past ecological thresholds

(Kooiman et al. 2005, Berkes et al. 2006).

- Patronage, when coupled with weak resource governance, external shocks and strong market demands, could contribute to eroding social-ecological resilience.

Typhoon Yolanda in November 2013, and the resulting aid interventions, lead to a number of internal changes within the fisheries of Concepcion, including a rise in the number of vessels (Hanley et al. 2014, Chamberlain 2015, Ong et al. 2015), a decrease in average vessel size, and increasing debt burdens of both fishers and trading agents, who took loans to re-start operations. This left fishers particularly more entrenched in the PC system than before. PC were quick and flexible to respond to the natural disaster aftermath, providing finance to rebuild vessels or to fuel newly donated vessels. These dynamics as well as the additional internal changes filtered by the PC system (i.e. income and catch fluctuations), are likely to have longer-term social and ecological impacts for Concepcion. Notably, when coupled with lack of law enforcement and local management capacities, as well as the prevalent economic vulnerability throughout households. For example, the PC system only enhances their adaptability to specific known shocks, e.g. income fluctuations, while the underlying causes of their economic vulnerability are not addressed, and this can decrease the overall system’s ability to deal with unknown shocks in the future (Walker et al. 2004, Nelson and Finan 2009).

Post-Yolanda Concepcion fisheries appear to be on a trajectory in which the SES is increasingly less able to support human and ecological wellbeing. Yolanda left badly damaged marine ecosystems in its wake (Granath 2014, Kent 2014, Campos et al. 2015). Meanwhile, inshore fishing effort has increased, which goes unregistered by many fishers who felt the situation was the same as pre-Yolanda. Additionally, the Concepcion fishery has been weakly governed and

experiencing declining stocks for a long time (Ferrer and Defiesta 2005, Ferrer 2016). The declining conditions, diversity and biomass of organisms translates into big risks for dependent fishers and patrons. Further, when SSF incorporate bigger market demands, e.g. regional, national or global, short-term economic incentives offered through fast responding PC have led to more intensive (and sometimes destructive) exploitation (Johnson 2010, Ferse et al. 2014, Nurdin and Grydehøj 2014, Miñarro et al. 2016). Debt is now more tightly coupled to fishing and ecosystem dynamics as both fishers and traders still have large post-Yolanda debts with their patrons. Coupled with the lack of alternative livelihoods in the area (Ferrer and Defiesta 2005) this change may only increase the dependency of local households on fishing. As a result of the PC system’s response to shock, actors’ indebtedness and reliance on informal institutions have expanded and changed the longer-term trajectory of the Concepcion system.

Full references can be found in the thesis PDF

This work was made possible through the generous contribution of SIDA (The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency) through Grant number 1425704, by MISTRA funding to the Stockholm Resilience Center Grant No. 1953001 and funding to the Global Economic Dynamics and the Biosphere program by the Erling-Persson Foundation