Access the article here: https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pan3.10742

FINALLY the first of my two papers from my Postdoc with the OctoPINTS project is out- its only took yeeeaaaaaars and two babies but its finally done! I made a very informal short video explaining the study in an accessible way (hopefully), see above, and below is a little summary. I was inspired by Wynand Boonstra and Dražen Cepić and their two great papers (including others) on compliance in different fishery settings; the papers being “The quality of compliance: investigating fishers’ responses towards regulation and authorities” and Justifying non-compliance: The morality of illegalities in small scale fisheries of Lake Victoria, East Africa. Reading their works reminded me of how the fishers and traders in Zanzibar had talked about (non-)compliance in a fishery closure- so I combined their theoretical frameworks and used them to code my work and explore the greyness of how people can respond to rules, rule-breakers and rule makers. And ultimately how this leads to support or not for marine protected areas.

This paper examines the complexities of compliance with marine conservation regulations using the case study of octopus fishery closures in Zanzibar, Tanzania. The research, informed by interpretive research ethics, explores how diverse groups of fishery stakeholders respond to regulations, justify their (non-)compliance, and how these factors impact conservation outcomes.

●While generally supportive of the closures due to recognition of a degraded marine ecosystem, different livelihood groups — including fisherwomen, fishermen, traderwomen, tradermen, and divers — displayed a range of motivational postures and justifications for (non-)compliance.

●The most common motivational posture observed was commitment, characterized by a sense of responsibility for upholding the rules and mobilizing others to accept the closures. This was particularly evident at one site (Site 2) where participants had experienced the benefits of the closures for a longer duration.

●Capitulation was another prevalent posture, where individuals accepted the closures due to the perceived benefits or lack of choice, despite potentially having reservations.

●The researchers also observed instances of creativity, mostly among divers who demonstrated a deep understanding of the rules and sought loopholes for personal gain.

●Justifications for (non-)compliance were primarily framed around ecological need, with participants highlighting the importance of closures based on their local ecological knowledge (LEK). This was in contrast to the principle of superfluousness where individuals believe the ecosystem is healthy and regulations are unnecessary.

●Another prominent driver of non-compliance was futility, evident in frustrations over lack of enforcement and the perception that rule-breaking is widespread, making compliance seem pointless.

●Contrary to expectations, autonomy — the desire to be free from state control — was rarely used to justify non-compliance. Instead, many participants called for greater state involvement (dependency) to ensure rule enforcement and legitimacy, particularly in the Pemba sites.

●Interestingly, socio-economic vulnerability was not typically used to justify non-compliance, but rather as a motivator for supporting the rules and ensuring compliance (provisioning). This was particularly important for female groups who relied on the closure benefits to meet basic needs, such as education expenses for their children.

The study highlights that compliance is not a binary concept, but rather a complex interplay of motivations, justifications, and social dynamics. It underscores the importance of understanding the diverse perspectives of stakeholders to develop more effective and equitable conservation interventions. The researchers recommend engaging with a wider range of stakeholders beyond just fishing organizations, taking time to listen to participants’ perspectives and reasonings around rules and rule-breaking, and employing a targeted approach that considers the specific needs and motivations of different groups.

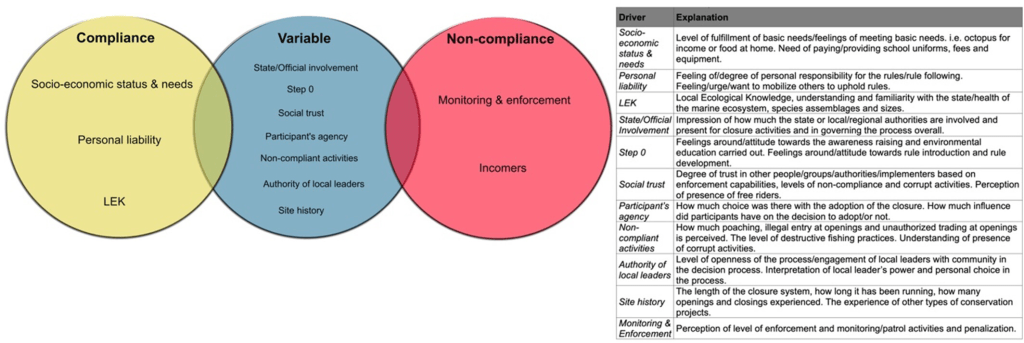

Overview of the drivers of different types of compliance outcomes in our dataset. Yellow represents what drives compliance only in our work, blue represents influencers that can cause variable outcomes, that is either non-compliance or compliance and the red circle shows what drives non-compliance only amongst our participants. Each of the drivers is explained in the accompanying table to the right of the circles

Leave a comment